Commodities Trading and

Transportation Management

Ray Sines looks like The Snowman. He’s got the cut-off vest, the mesh-backed trucker hat and he’s made of the same good-natured Appalachia gristle. Where the Coors-totting Texarkana bootlegger Cledus Snowman dodged the nasty deep-south law to deliver sweet sudsy beer to an Atlanta fair in the movie Smokey and the Bandit, Ray dodges genocide-minded Sudanese militia and stuffs banana mash into busted differtials to deliver rundown trucks from Kenya to the UN peacekeeping mission in South Sudan.

Not everyone has as much fun in their logistics careers. Ray and his business partner Ian Cox operate in the “Wild West” of developing Africa. In 2013, they were filmed for a documentary series, “Africa’s Cowboy Capitalists”. In this cowboy landscape, laws are loosely followed, and police records are stored in big bundles and left to collect dust under the East African sky. Outside of a backwash Ugandan border town, a flatbed in their rickety convoy is hit head-on by a drunk driver. The drunk man walks free without even the suggestion of a BAC test while the police make up their own version of events and take a keen interest in the structural integrity of the trucks.

In these operating environments it can be tempting to do things the local way. When deals go south for the winter in East Africa, smooth talking and a well placed palm of silver will get you a lot farther than a combed-over a white shoe lawyer eager to tussle over the minutiae of interstate commerce legalese. For fly-by-night operations working on the fringes of the world economy, that might be an acceptable practice, but for big international companies with headquarters in Western countries, these situations present no good options. Either you stick to the letter of the law, cover your rear back home, and go absolutely nowhere with your operating goals, or you do things “the local way” and expose yourself to a corruption charge.

Operators must choose between one risk or another. The way that operations play out on the ground can have very serious financial, legal, public relations, regulatory and operating consequences. One tried and true tactic of big companies operating in these “wild west” locations in the developing world is to use well-connected middle men, or cut-outs. These can provide at least some protection from allegations of corruption. Another option is to build and own all of the operations directly. With this path, companies can directly manage the chaos of local bureaucracy and can find more indirect ways to create mutually beneficial arrangements that will pass the bribery litmus test back home. While difficult, successfully managing these challenges can bring large rewards.

These difficult scenarios are a key crossroads between big commodities firms and the transportation management business. Not all commodities companies choose to operate transportation management businesses, and those that do are not necessarily limited to free wheeling markets in developing nations. Louis Dreyfus, for example, owns significant operations and infrastructure across the United States while Trafigura operates large logistics terminals in southern Spain. In addition, transportation assets can provide benefits besides political risk management. To better understand the full role of transportation businesses in the overall strategy of commodities firms, this essay investigates the three following questions:

1.) What are the challenges facing commodities firms?

2.) What benefits could these companies receive by operating directly in the transportation management business?

3.) What alternatives are available to commodities firms in the transportation management space?

In order to answer the questions posed above, this paper will first provide some historical background on the industry. From there the paper will examine the challenges that face these organizations. Those challenges are as follows:

1.) Democratization of Information

2.) Corporatization

3.) Compliance in a Developed World

4.) Platforms and Technology

5.) Capital Intensivity

After discussing the challenges faced by these firms, the essay will outline some of the benefits available to commodities firms that choose to take a more active role in the transportation functions of the commodities business. Through the discussion of benefits, the essay will examine several case studies from commodities firms in the transportation industry. That section will follow the outline below:

1.) Optionality

2.) Warehouse Squeezes

3.) Data Access and Market Understanding

4.) Service Value to Customer

5.) Cost Management

6.) Transparency

Historical Context

Before discussing the development of commodities firms in transportation management businesses, a distinction must be made between agricultural traders on one hand and oil and metals traders on the other. The contrasts in the operating environments and market dynamics of the two industries mean that any historical analysis must evaluate them separately.

The world’s largest agricultural traders are all American, and, as far as businesses go, they are quite old. Archer Daniels Midland was founded in 1902, Bunge in 1818, Cargill in 1865, and Louis Dreyfus in 1851, there is also Koch Industries, which was founded in 1940. The balance of power between supplies and traders in the Agricultural sector is the complete opposite from energy and mining. Where oil has or has had its seven sisters, its “majors”, and where oil companies roost comfortably in the top ranks of the world’s largest companies, there are no big farmers that can match the scale of the big agricultural traders. In a situation reminiscent of the relationship between farmers and the railroads in the 19th century, the size differential between traders and growers translates into large disparities in access to capital and market power. The big traders have historically deployed capital to control much of the key infrastructure of transportation such as silos, warehouses, logistics facilities and processing plants. Unlike the oil market, this pattern has a history stretching back over 100 years. In fact, complaints of traders controlling grain elevators and trading infrastructure go back to the mid 19th century.

The story for oil and metals traders is quite different, for one the history of the modern oil/metals trader largely begins in the 1970s. Culturally and politically, the 1970’s were a chaotic time for the West, in particular the United States. The decade dawned on the still-burning conflict in Vietnam. Before the decade wrapped, it would witness the OPEC oil embargo; the Watergate scandal; the rise of a new anti-social youth culture; general urban decline, including New York City’s bankruptcy; increased Soviet power; and a waterfall of coups, rebellions, revolutions and wars that challenged a world order based on rule of law, democracy and human rights.

In the business world, events were perhaps less melodramatic but just as exciting. While computers began their march into the office and formed a beachhead in the home through new personal computers, big oil accelerated its exit from sales and trading operations in order to focus on the capital-intensive upstream exploration and production activities.

This divestment opened the door for traders, many who had formerly operated at the margins where the majors didn’t bother to participate. Of the top 10 independent trading companies in the oil and metals space today, not one existed before 1966 and most took off in the mid 1970s. While oil trading is very distinct from trading in metals, condensates, and ore, the fortunes of the biggest metals traders historically flowed from the success of earlier oil trading businesses. Glencore, the biggest metals trader of today, got its start in oil. This pattern of expanding into metals from a successful foundation in oil trading was later repeated by Trafigura and Mercuria.

The transition into owning physical assets happened gradually over a period beginning roughly in the 1990’s, as these companies experienced a period of high growth and expanded availability of capital that opened to door to strategies that involved owning assets. However, the companies’ pattern is characterized by swift entry and exit. Investments in physical assets and transportation businesses are strategic in nature for commodities firms, that is they have had little interest in the long term operation of these assets, but rather they view transportation businesses from the point of view of a trader. Their role in the business is to serve the trading objective, and the success or lack thereof is measured primarily by their ability to provide gains to trading activities.

That paradigm may be changing. Because of the pressures that will be discussed in the challenges section, oil and metals traders have started to change their strategies to more closely resemble their agricultural cousins. Glencore is a notable example. It focuses its energy on metals, and at this point has effectively evolved into an integrated mining company, more similar in structure to BP or Shell than its peers in the trading space. One of the historical drivers of that shift was the aggressive invasion and then sudden retreat of the large American investment banks into the commodities trading arena.

Beginning in the early 2000’s investment banks, notably Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley, started expanding their participation in the physical trading of commodities. The banks were well situated to compete with established traders, as they had unrivaled access to capital, customers, market information, technology and political clout. This period brought brought about some now-legendary trades such as the “Aluminum Shuffle”, where Goldman circumvented legislation designed to prevent market fixing by having truckers move 3% of the world’s refined aluminum back and forth between rust belt warehouses. The resulting corner cost consumers up to $5 billion dollars. The relevant detail for the purposes of this research is that the banks’ activities put significant pressure on existing traders in part by buying up physical assets and pushing the less-well capitalized players to the fringe. In the case of the Aluminum shuffle, Goldman choose to own the warehouses outright. Old line traders like Castleton, Mercuria, Noble and Rusal got a break in the 2007 financial crisis. In the ensuring storm of regulation and fines, banks were legally and financially forced out of physical commodities markets, and the traders were positioned to buy up some of the banks’ assets and expand into the new business left behind.

In the years since then, it appears that at least some of the commodities giants have changed their attitude towards owning and operating physical assets. Glencore’s integration was already mentioned, but Trafigura has also made some steps in that direction. It has a subsidiary, Impala Terminals, which it has integrated into its financial reporting, website and company materials in such a way as to suggest a long term interest in the business. It has already owned the business since 2001, further supporting the argument of a change in strategy. On the other hand, it has recently disclosed a Joint Venture with IFM Investors, in which the latter would take on 50% ownership in Impala and would commit to investments to grow Impala’s presence in South America. It remains to be seen whether Trafigura will exit its investment in Impala or continue to grow its logistics operations, but whatever the outcome, Impala’s fate will be a significant bellwether for the future of commodities trader’s strategies with regards to the transportation businesses.

Challenges

“Everything is transparent, everybody knows everything”

-Daniel Jaeggi, president of Mercuria Energy Group Ltd

Democratization

A small firm in Palo Alto is spying on the world’s oil storage tanks. The Company, Orbital Insight, uses satellite images and machine learning to identify and measure the amount of oil kept in storage at facilities around the world. Oil tanks use floating roofs in order to prevent highly volatile vapor from forming, and therefore the shadow cast by the container over the tank roof is an indicator of how much oil is stored in that tank. The company measures the shadows cast by the tanks and generates reports on oil reserves that beat official reporting by weeks. Orbital sells this information to energy traders, producers, refiners, hedge funds and any market participant who is willing to pay. While this development is great for buyers and sellers, it puts pressure on the traders who used to have privileged access to this sort of information. Orbital is just one of many new analytics firms entering the commodities market armed with data and analytics tools. This democratization of data has reduced the opportunity for traders to make gains based on unique access to information.

The democratization of information means that the trader can no longer exploit knowledge differentials between buyer and seller in order to extract bigger margins on a trade. That information asymmetry is the bread and butter of traders of all kinds, from used cars to insurance. In fact, the increased access to information by refiners and sellers might be compared to the emergence of services like Carfax, which gives otherwise uninformed consumers precise information on the value of their vehicle. When pressure is applied to this source of margin, the business must look then look elsewhere to drive profitability. This challenge is particularly acute in the context of the industry’s history, which is undergoing a shift from loosely affiliated trading pools under the veneer of a corporate partnership to professionalized and highly institutionalized corporations.

Corporatization

Traditionally, physical commodities trading is a game of routine business on the one hand and slam dunk windfalls on the other. Firms have historically chosen to operate as affiliated “pools” of extremely successful traders. Much like a doctor’s office, these independent operators choose to combine their resources to spread the costs of back and middle office functions like accounting and demurrage desks. In addition, the traders had better access to capital as a collective as banks viewed the larger pools as more diversified and therefore better credit.

These loose federations where always unstable. A disgruntled trader found it very easy to pick up his client book and move to a rival firm or start up on his own. Successful traders enjoyed a sort of legendary status that promoted cults of personality. Andy Hall, a star trader originally at Citibank, is known in the business by the nickname “God”. God is well known for earning a $100 million bonus in the middle of 2008 and drawing the ire of politicians and the media. “God” went on to found a hedge fund in 2010 with $3 billion of investment. That firm was forced to close its doors in 2017 after its marquee fund lost 30% in the first half of that year. The case of Andy Hall is typical of the old way of doing business. The system rewards large bets and high risks, as the traders do not stand to lose their own wealth in a bad trade, but stand to gain significantly when trades go well.

With brand name traders no longer able to bring in the returns expected due to the pressures already discussed, companies have begun to move away from the old model and towards a more corporatized, institutional model. Traders are paid well, but their packages have shrunk considerably, there is more of an emphasis on managing deals through teams rather than through a single contact point. This institutionalized approach, however, leaves companies with a problem of recapturing margins. These new models may reduce risk and large payouts to star traders, but they do not help companies looking to regain the high margin business that the star traders were once so good at reeling in.

Compliance in A Developed World

Volatility comes in many forms, and it is the trader’s job to manage the risks that underpin volatility. In fact, traders need volatility in part because with big swings on price and big risks associated with trading, come outsized margins. Marc Rich, the legendary founder of Glencore, made just such profits bypassing US sanctions on Iran to buy their oil and give them access to much needed cash. Putting the glaring ethical and legal issues aside, this example is somewhat typical of extremely lucrative trading deals that once powered the big commodities firms. Wars, terrorist attacks, coups, political crises, hurricanes, tsunamis, sanctions and so on provide opportunities for traders willing to take on the relevant risk.

Global political volatility may very well be on the rise, offering opportunities to traders, but as industrialization and development continue to spread, “developing” countries continue to transition into the ranks of the “middle income” nations. As they do so, these countries are more and more able to tap into the international banking and financial markets for access to capital. As former metal trader Brian Scher explained in a recent interview, In the not so distant past, countries like Thailand were effectively cut out of financial markets; they relied on commodities traders for much needed cash in exchange for natural resources. Banks were willing to lend to the traders, confident in their ability to extract the underlying commodity from the country and make good on the credit. Now, banks are more comfortable working directly with middle income countries.

In addition, the institutions that police corporate behavior have recently become more aggressive. Traders are under increasing scrutiny internationally. One source described the situation thus:

“Not since the days of fugitive oil merchant Marc Rich has the commodities trading industry faced so much global scrutiny. The biggest independent oil and metals trading houses, including Vitol Group, Trafigura Group Ltd., Glencore Plc., Mercuria Energy Group Ltd. and Gunvor Group Ltd., are facing bribery and corruption investigations in jurisdictions ranging from Brazil to Switzerland and, most importantly, the U.S.”

Trafigura has come under fire multiple times in recent years. In one case, Trafigura’s CEO found himself languishing in an Ivory Coast prison for over five months because of a pollution incident involving one of its subcontractors. It appears that there is a lower tolerance for misbehavior and an increased willingness to confront perceived wrongdoing that may make it more difficult for traders to navigate ethically complex business environments going forward.

Platforms and Technology

Besides the intrusion of new sources of data, technology has made inroads into the methods by which buyers and sellers connect. For example, platforms have begun to creep into the commodities space. One such notable platform is Farmlead, but there are many others, including Open Mineral, SourceSage, MySteel, Uber Freight and Helixtap. On these platforms, sellers post what they are looking to sell and buyers can browse and bid at the click of a few buttons. While these platforms have not yet achieved the same success in the commodities industry as they have seen in consumer-oriented markets, the big commodities firms are well aware of the threat they pose. Trafigura has developed its own platform for refined metals called Lykos, and many of the biggest customers of the platforms named above are commodities giants like Archer Daniels Midland and Rio Tinto.

Capital Intensivity

New technology demands are pressuring firms to expand on data security, automation, payment systems, and risk measurement. In order to keep up, commodities firms are going to need to invest heavily. Trafigure has invested $500 million dollars in the past five years alone on technology. One of those new assets is the Lykos platform, but the company has also invested heavily in proprietary data analytics systems, risk measurement software, credit systems, and human resources applications.

In addition to technological investments, commodities firms require significant short term capital in order to finance thousands of trades that may add up to hundreds of billions of dollars. These trades are short term and backed by highly liquid commodities, but when markets are strained, there is a “flight to quality”; banks become reluctant to lend to any but the biggest and most established players. Trafigura’s own 2018 annual report concedes:

“We expect the market environment to remain challenging in some respects, especially as the global interest rate cycle continues slowly to ratchet upwards and banks become more selective in deploying credit beyond the leading firms in the sector.”

Having discussed the challenges facing commodities firms, the profile of benefits available to commodities firms will now be analyzed. For the purposes of focus and academic relevance, the discussion will focus only on the benefits enjoyed from investments and operations within the space of transportation management.

Benefits

Optionality

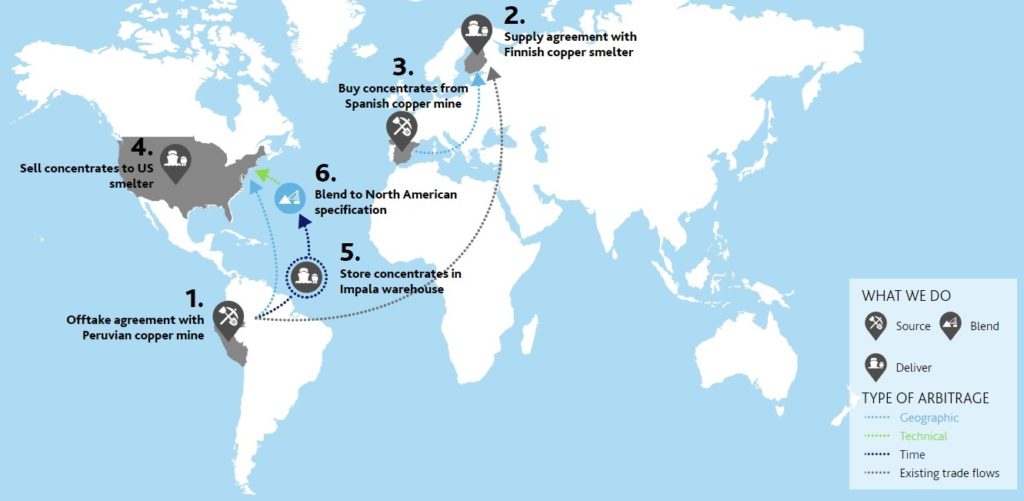

Traders can make more money by having more choices available to them on how to procure, store, blend and ship commodities. Owning a transportation business outright gives traders the best possible access to those options. Here is a classic example of optionality as explained by Trafigura’s own material on physical arbitrage.

In this example, the company enters into an offtake agreement for Peruvian copper, which it would close out by selling the copper to a smelter in Finland. As time goes on, the trader may identify an opportunity to blend the Peruvian copper into a new form at a blender it owns through Impala Terminals in Colombia, and sell it at a higher price to a smelter in the United States. In order to fulfill its obligation to the Finnish smelter, it sources copper from a Spanish mine. In this example, the company stands to profit by reducing transportation costs between supply and demand, as well as taking advantage of an opportunity it might not have otherwise been able to execute on if it were not for the Impala blender.

In this example the Impala terminal is key. Without the ability to quickly make use of that asset, the trader is powerless to take advantage of the new opportunity. It might occur to some that it is not necessary to own the blender and warehouse outright, Trafigura might simply rent out space at an available facility. That is an option that traders often take advantage of, however it poses some serious challenges.

Warehouse Squeezes

When Goldman began to buy up warehouses in Cleveland to shuttle aluminum back and forth, it was not the only market participant aware of the opportunity. Many traders piled into the play, but most did not have access to capital to buy warehouses and logistics firms outright; they instead relied on services provided by local businesses and Goldman Sachs. In this latter situation, traders were in a position where they needed to get product out of a warehouse owned by their direct competitor. As can be imagined, Goldman was less than helpful with their competitors’ business needs. In a recent interview, former trader Brian Scher discussed his experience trying to extract lead from the back of a Goldman-owned warehouse in Cincinnati.

“That aluminum play was an amazing trade, and everyone was in on it. We were doing the same thing with lead, but Goldman owned the warehouse, and they would keep pushing our product to the back of the line [for shipments out of the warehouse]. My boss complained to the LME (London Metals Exchange), and the LME actually changed its rules so that they had to let a certain amount of material owned by other traders out each day. Luckily, we were in lead, so we got to go right to the top of the list.”

In this case, while the lead was eventually extracted from the warehouse, the traders were under considerable strain as they had commitments to deliver the lead to a buyer in the Midwest. Without the timely interference from the LME, the Goldman’s squeeze may well have cost the company millions of dollars in lost revenues and damaged relationships. These sorts of strong arm-tactics are best circumvented by simply owning the asset directly. However, this logic only applies in tight markets where the available space is owned by potentially non-cooperative competitors.

Traders will be most likely to buy a warehouse in a strategic location where they can maximize the asset’s utility vis-a-vis optionality. For example, Trafigura’s Colombian Impala warehouses are well placed to receive the significant and varied flows of metal concentrates that arrive from mines in Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Peru, and Bolivia. It is no accident therefore, that the majority of Trafigura’s warehouse assets are located near multiple sources of raw material.

Data Access/ Market Understanding

In order to make wise business decisions and inform the exercise of optionality discussed above, traders need access to market data about the flows and levels of various products as well as insights into the conventions and operating procedures within related markets such as bulk shipping or trucking. In the former case, traders have discovered that trading in ships, that is buying and selling the fixtures as one might buy and sell barrels of oil, is a profitable business in its own right. Bringing any kind of business in-house, whether it is a refiner, a warehouse, another trading firm, or a logistics company, will offer the new owner access to all of the financial and market data of the acquired business. For traders, this information edge is key to making smart deals, and in some cases, traders will choose to take a very small position in a company, around 1%, in order to gain access to the data. These deals are often simply glorified offtake agreements where the trader is agreeing to buy most or all of the production of a mine or refiner. In some cases, the trader may act as a lender rather than an equity investor. In a 2018 deal recently closed between Mercuria and Romanian miner Vast Resources, Mercuria extend $9.5 million in loans to the zinc and copper miner as part of a 100% offtake agreement. As a lender, Mercuria will have unique access into the company’s proprietary financial and operating data that they might not have otherwise had access to.

This same strategy applies to assets in the midstream. Pipelines, terminals, refiners, storage facilities, shippers and inland logistics all have unique access to market information that, in the right hands, can translate into trading opportunities.

Service Value to Customer

By bringing logistical activities in-house, the trader is able to provide an extended suite of services to their customers. If a client needs a certain shipment stored and delivered at a later date, a company with well positioned warehouse assets will stand to benefit over another that must scramble to find a third party willing to participate in the deal. In strong-arm environments like those discussed earlier, owning the asset directly may be critical to winning and retaining business. The challenges section investigated numerous pressures faced by commodities traders on their margins, including the fading of the big stars and the movement towards lower margin, institutionalized business models. One solution to those challenges is to provide a more complete suite of services to the client. Much in the same way that a cruise ship might find significant margins by providing upscale services, commodities traders can recover those pressured margins by offering a suite of services that their competitors can not offer. At a recent roundtable discussion on the commodities market, panelists, including executive officers at some of the largest trading firms in the world responded to the pressures thus:

“The traders highlighted the need to more than simply buy and sell commodities as profits from arbitrage — or gains made from a differential in prices — shrinks. That means getting involved in the supply chain by potentially buying into infrastructure that’s key to the production and distribution of raw materials, and also providing financing for the development of such asset.”

One such service comes in the form of Blockchain payment and tracking systems. Blockchain is particularly interesting as it straddles the business, facilitating both financing and transportation management. In it’s 2018 Annual report, Louis Dreyfus announced that it had successfully completed the first full cycle agri-commodity transaction. It did so in conjunction with financial partners ING, Societe Generale and ABN Amro and buyer Shandong Bohi Industry Co. Louis Dreyfus writes:

“All aspects of the operation were conducted through the blockchain platform, designed to accommodate the sector’s complex and rigorous documentation flows with a full set of digital documents (sales contract, letter of credit, certificates) and automatic data matching, thus avoiding task duplication and manual checks, and allowing real-time progress monitoring, data verification, reduced risk of fraud and a shorter cash cycle.”

Louis Dreyfus’ breathless evaluation of the process comes from two key benefits. First there is the service value to the customer. Dreyfus can now offer simple, powerful solutions to its customers that its competitors can not compete with. By offering these cutting edge solutions, Dreyfus positions itself to capture more market share. Additionally, Blockchain will help Louis Dreyfus cut its back office expenditures.

Cost Center to Be Squeezed

To this day, almost all commodity transactions fall back on paper documents that must be carefully read, signed and passed back and forth between the traders, their customers and each party’s bank. This manual process is labor intensive and is one of the largest costs that traders must manage. Blockchain technology, which does most of the heavy lifting digitally and with minimal input from the participants, will open up margin on trades that is being squeezed by technology elsewhere.

In the field, commodities traders are often able to professionalize operations and reduce risks as compared to using grey market intermediaries and third party contractors. Take for example the Trafigura pollution crisis in the Ivory Coast. The company had contracted the disposal of the ship’s waste to a third party which simply dumped the waste near a large population center. As mentioned earlier, the firm’s executive management spent several months in prison and Trafigura ended up paying almost $200 million in fines to the Ivory Coast. These sorts of incidents are common when working with third parties, but are nearly unheard of when the operations are run by the trader. In an environment of rising regulatory scrutiny, traders can bypass the black swan risks by bringing operations in-house. This cost cutting can then be passed along to the customer to capture market share or it can be retained in order to pad margins.

Transparency

Commodities traders have had a bad reputation in the press. Documentaries and news reports about them almost invariably lead with suggestive questions about their legitimacy as valuable actors in the free market system or else highlight the industry’s scandals or historical secrecy.

In response, some participants in the market have decided to opt voluntarily for greater transparency. The reader may note a heavy reliance of this report on details pertaining to Trafigura. That is in no small part because the company, which is entirely privately owned, has made a commitment to transparency, going as far as to publish complete financial statements and interim reports as if it were publicly traded. While not all traders have followed suit, there has been a rising tide of transparency in the industry. Louis Dreyfus publishes a host of sustainability reports in addition to its required financial reporting and Glencore publishes limited financial results and discloses its payments to governments in a new annual report.

In transportation management, a trader is going to have a hard time with operations transparency as long as it works with third parties. Trafigura’s Impala business highlights its investments in participating countries. By bringing money into the country in the form of investments, companies can reframe its operations in a country. These strategies reallocate potentially risky payments to government officials into infrastructure projects that benefit wider a wider subset of the community while alleviating some of the pressure to pay bribes at an operational level. Also, having a long term commitment in a country make it logical to develop deeper relationships with the government. Firms can opt to make direct payments to governments, as in the case of Glencore. If the funds are then embezzled, that malfeasance is no longer the responsibility of the trader.

Conclusion

The commodities business is in transition, and its leaders are looking for creative solutions to the challenges they face. Many of those challenges come from technology, which is also the source of some of the industry’s most promising options. Still other challenges relate to an industry moving away from its cowboy days and into the civilized world of streamlined, multinational institutions. In both cases, it is the bigger companies who are going to survive the next phase of the industry’s history. How will transportation management fit into that evolution?

Transportation businesses offer a range of benefits for commodities traders, as discussed in depth earlier. However, these assets don’t come cheap, and more than a few companies have found themselves with large piles of debt after binging on midstream and downstream businesses and assets. The volatile nature of the industry can also make pricing and valuation a difficult process. Famed commodities trader Noble nearly went into bankruptcy after a short seller released damning research about the companies accounting practices related to its acquisition of a portfolio of midstream gas businesses in 2015. That same short seller recently turned its sight on Trafigura in relation to its acquisition of port terminals in Brazil:

“The analyst who brought about the near collapse of Noble Group has turned his attention to Trafigura, a much bigger commodity trader that in his opinion has been inflating the value of assets to help manage a huge debt pile. In a report published on Wednesday, Arnaud Vagner, who writes under the name of Iceberg Research, argued that Trafigura had ignored “economic reality” to “aggressively overvalue” debt securities issued by Porto Sudeste, a Brazilian iron ore terminal it controls.”

Managing multi-billion dollar international businesses is an incredibly difficult responsibility allocated to only the most competent and energetic of the world’s human resources. As the commodities trading industry confronts the current raft of difficulties, they might well consider taking a careful look at expanding their operational assets in the midstream and logistics spaces. In order to do so without undermining their financial security, these firms ought to continue to rely on extensive partnerships and joint ventures, allowing them to focus on their core trading activities. This strategy will ensure substantial flexibility to deal with the industry as it evolves and faces new challenges.